0

0

Can AI spot age-related macular degeneration better if it learns from eye pictures instead of cat pictures?

Benchmarking Ophthalmology Foundation Models for Clinically Significant Age Macular Degeneration Detection

Get notified when new papers like this one come out!

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of irreversible vision loss in adults over 40, affecting 12.6% of US adults and projected to impact 288 million people globally by 2040. This condition impairs central vision, significantly affecting daily activities like reading, driving, and facial recognition. Current diagnostic methods rely on specialized ophthalmic examinations, limiting accessibility in many regions.

Deep learning has emerged as a reliable tool for automated identification of eye diseases from retinal scans. Self-supervised learning (SSL) enables Vision Transformers (ViTs) to learn robust representations from large-scale datasets without explicit annotations, creating foundation models that can be efficiently fine-tuned for specific tasks with limited labeled data.

While foundation models pretrained on both natural and ophthalmic images have shown promise in retinal image analysis, it remains unclear whether in-domain pretraining provides significant advantages over using natural images. This research investigates this question by benchmarking six SSL-pretrained ViTs for identifying clinically significant AMD from digital fundus images (DFIs).

The study makes three key contributions: (1) a comprehensive benchmark of foundation models for AMD detection, (2) development of AMDNet, an improved model for AMD identification, and (3) release of BRAMD, a new open-access dataset of DFIs with AMD labels from Brazil. This work builds on recent advances in vision-language foundation models for ocular applications.

The Challenge of AMD Detection and Dataset Curation

AMD detection represents a significant clinical challenge, particularly in its moderate to late stages when the risk of vision loss increases substantially. The researchers curated a comprehensive collection of 70,523 DFIs from seven independent datasets encompassing diverse imaging conditions and fields of view.

The collection includes six publicly available datasets and one newly introduced dataset. Images were classified into two categories: intermediate-to-late AMD (including wet AMD, geographic atrophy, or large drusen) and non-intermediate-to-late AMD.

A key contribution is the introduction of BRAMD, a new dataset developed in collaboration with São Paulo Federal University. BRAMD includes 587 DFIs from 472 patients, with 295 images showing AMD and 292 control images from diabetic retinopathy patients. Diagnoses were confirmed through clinical examinations supported by OCT scans. This dataset has been made publicly available on PhysioNet.

The largest dataset used is AREDS, comprising over 200,000 DFIs from 4,757 patients across 12 US eye clinics. The researchers selected macula-centered color stereo images totaling 140,000 images. After applying quality criteria and exclusions, they retained 62,769 images, split into AREDS-train (90%) and AREDS-test (10%), ensuring no patient overlap between subsets.

Five additional datasets were included: RFMiD1 (3,200 DFIs from India), HYAMD (1,570 DFIs from Israel), ADAM (1,200 DFIs from China), FIVES (800 high-quality DFIs from China), and STARE (397 fundus images from the US). This diverse collection ensures robust evaluation across different populations, imaging conditions, and devices.

Methodology: Foundation Models and Training Approaches

The researchers benchmarked six state-of-the-art deep learning models fine-tuned on AREDS-train. Their methodology involved standardized preprocessing, comprehensive model evaluation, and development of a multi-source domain training approach.

Data preprocessing consisted of cropping images to remove unnecessary background, padding to form square layouts while maintaining aspect ratios, and resizing to 518×518 pixels using bilinear interpolation. This standardization was essential for handling images from various sources with different resolutions.

Six foundation models were evaluated: four pretrained on natural images (MAE, Mugs, iBOT, and DINOv2) and two pretrained on retinal images (RETFound and VisionFM). These models differ in architecture, parameters, and pretraining approaches, as detailed in Table 3.

All models were fine-tuned on AREDS-train for 10 epochs with a batch size of 20 DFIs, using learning rates from 1e-5 to 3e-4, weight decay of 0.05, and a cosine learning rate scheduler. Data augmentation included random horizontal flips and adjustments to contrast, saturation, and hue. A baseline ViT-L with standard initialization was also included for comparison.

After identifying the best performing foundation model based on average AUROC performance, the researchers employed a multi-source domain training approach. This involved training the model on all but one dataset, with the left-out dataset used as the target domain for evaluation. This leave-one-domain-out strategy allowed assessment of generalization performance across unseen datasets.

To address dataset size imbalances, the validation set contained comparable numbers of images from each training dataset. A class-weighted cross-entropy loss function ensured equal contribution from each class. This approach builds on methodologies developed for other medical imaging domains, as seen in research on scalable foundation models for digital dermatology and disease-specific foundation models.

The resulting best-performing model, AMDNet, was benchmarked against DeepSeeNet, a state-of-the-art open-source model for AMD detection.

Performance Results and Model Comparison

The performance evaluation revealed interesting patterns across foundation models and training approaches. Table 4 summarizes the AUROC values for all seven models (six foundation models plus baseline ViT-L) across the seven datasets.

Overall, foundation models significantly outperformed the baseline ViT-L (p<0.05) with an average performance improvement of 8%. Among the six foundation models benchmarked, iBOT achieved the highest average AUROC of 0.890 across all test datasets, slightly outperforming DINOv2 which obtained 0.888.

Figure 1: Models performance for AMD identification. (a) Results for foundation models fine-tuned on AREDS-train. (b) AMDNet performance comparison with DeepSeeNet.

Figure 1: Models performance for AMD identification. (a) Results for foundation models fine-tuned on AREDS-train. (b) AMDNet performance comparison with DeepSeeNet.

A key finding was that foundation models pretrained on natural images outperformed domain-specific models in five out of six target domains. Only in the case of BRAMD did VisionFM (pretrained on retinal images) outperform the general foundation models. This challenges the common assumption that in-domain pretraining is necessary for optimal performance in medical imaging tasks.

The best foundation model, iBOT, was further enhanced using the multi-source domain approach to create AMDNet. When comparing AMDNet to iBOT fine-tuned on the single-source domain AREDS-train, the researchers found that AMDNet improved performance by 4.7%. Even more impressively, when compared to DeepSeeNet, AMDNet demonstrated significantly superior performance, achieving an AUROC 10.2% higher on average.

These results align with recent research on adapting natural domain foundation models for medical imaging applications, suggesting that the representations learned from diverse natural images can transfer effectively to specialized domains like ophthalmology.

Error Analysis and Explainability

The researchers conducted a comprehensive error analysis to understand the model's performance across different AMD subgroups, demographic variables, and comorbidities.

The model achieved varying performance across AMD subgroups: an AUROC of 0.930 for Large Drusen (LD) versus 0.998 for Geographic Atrophy (GA) and 0.980 for Neovascular AMD (NVAMD). This indicates greater difficulty in identifying LD compared to the other more advanced AMD subgroups.

Figure 2: Error analysis. a) AMDNet probability output for different AMD subgroups; b) AUROC per age group; c) False positive rate per comorbidity.

Figure 2: Error analysis. a) AMDNet probability output for different AMD subgroups; b) AUROC per age group; c) False positive rate per comorbidity.

Performance analysis across demographic variables showed consistently high AUROC scores for both sexes: 0.975 for male patients and 0.979 for female patients, indicating no significant sex-based differences in classification outcomes. For age groups, the model achieved its highest AUROC of 0.981 for patients over 85 years old, with slightly lower performance in younger age groups (0.972 for 18-70 and 0.979 for 70-80).

Figure 3: AUROC performance stratified by age groups for the BRAMD dataset.

Figure 3: AUROC performance stratified by age groups for the BRAMD dataset.

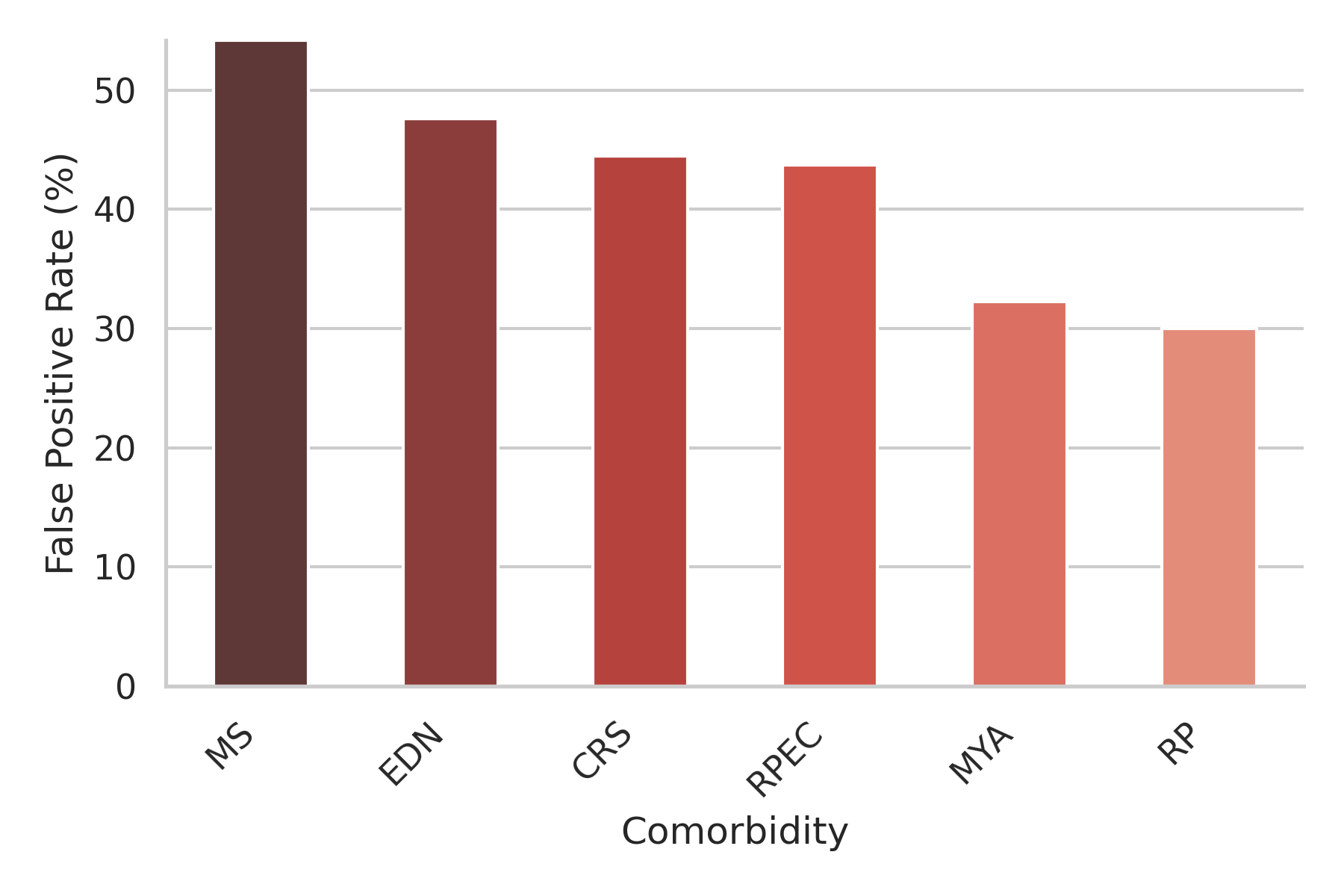

Analysis of comorbidities revealed that certain conditions were more likely to produce false positives. The most prevalent comorbidities among false positives were Macular Scar (54.2%), Exudation (48.6%), Chorioretinitis (44.4%), Retinal pigment epithelium changes (43.8%), Myopia (42.3%), and retinitis pigmentosa (30.0%). These conditions often affect the retina in ways that can mimic AMD features.

Figure 4: False positive rates across different comorbidities in the RFMiD1 dataset.

Figure 4: False positive rates across different comorbidities in the RFMiD1 dataset.

To visualize the model's decision-making process, the researchers used GradCAM to generate attention maps. These maps showed that AMDNet consistently focuses on the macula, even in healthy images. The model accurately detected lesions such as LD, GA, and NVAMD, as shown in the examples below:

Figure 5: (a) Retina without AMD. p=0.04

Figure 5: (a) Retina without AMD. p=0.04

Figure 6: (b) Retina with Large Drusen. p=0.99

Figure 6: (b) Retina with Large Drusen. p=0.99

Figure 7: (c) Retina with GA. p=0.96

Figure 7: (c) Retina with GA. p=0.96

Figure 8: (d) Retina with NVAMD. p=0.68

Figure 8: (d) Retina with NVAMD. p=0.68

Discussion and Clinical Implications

The benchmark of six foundation models for AMD identification yielded several surprising findings with important clinical implications. Most notably, iBOT, a foundation model pretrained on natural images, exhibited superior out-of-distribution generalization compared to domain-specific models like RETFound and VisionFM.

This challenges the common assumption that in-domain pretraining is necessary for optimal performance in medical imaging tasks. The finding confirms earlier observations where DINOv2 (pretrained on natural images) yielded better outcomes for diabetic retinopathy staging and glaucoma identification compared to models pretrained on retinal images. Recent research by Xiong et al. also found no statistically significant improvement when using RETFound compared to models pretrained on ImageNet for glaucoma and coronary heart disease diagnosis.

The development of AMDNet demonstrates the value of combining a strong foundation model (iBOT) with a multi-source training approach. This approach, which trains models on multiple datasets while leaving one out for evaluation, significantly improves out-of-distribution generalization, a critical factor for real-world clinical deployment.

Error analysis revealed that AMDNet performs best on advanced AMD subgroups (GA and NVAMD) versus the LD subgroup. This is clinically coherent, as GA presents as visible atrophy with well-demarcated, brighter abnormal lesions, making it easier to detect than early-stage changes. The analysis also showed that false positives were associated with comorbidities that can mimic AMD features, particularly those affecting the macula or causing changes in pigmentation.

Performance across different age groups showed a slight trend of increasing accuracy with patient age, likely explained by the age-related nature of AMD: older patients often exhibit more advanced disease stages, which are typically easier for the model to detect.

The detection of AMD in DFIs has gained increasing attention, driven by advances in imaging technology and computational analysis. These automated systems mitigate inter-observer variability inherent in manual interpretations and allow for early detection, crucial for timely intervention. Integration with telemedicine platforms has expanded accessibility to AMD screening, particularly in underserved regions lacking specialized ophthalmic services.

Prior studies have often focused on single-population datasets, limiting evaluation across diverse populations and clinical settings. The comprehensive multi-dataset approach used in this study, with the resulting AMDNet model achieving AUROCs of 0.842-0.977 across different datasets, represents a significant step toward creating robust, clinically applicable AI systems for AMD detection. These findings align with ongoing efforts to develop high-performance retinal foundation models that can generalize across diverse patient populations and clinical settings.

Conclusion

This comprehensive benchmarking study of foundation models for AMD detection yields several important conclusions with significant implications for both research and clinical practice.

First, foundation models pretrained on natural images outperformed domain-specific models pretrained on retinal images for the task of identifying clinically significant AMD. The iBOT model achieved the highest average AUROC of 0.890 across all test datasets, challenging the assumption that in-domain pretraining is necessary for optimal performance in medical imaging tasks.

Second, multi-source domain training significantly enhances model generalization. AMDNet, created by fine-tuning iBOT using a leave-one-domain-out approach, improved performance by 4.7% compared to iBOT trained on a single dataset, and by 10.2% compared to the state-of-the-art DeepSeeNet model.

Third, models show varying performance across AMD subgroups, with better detection of advanced stages (Geographic Atrophy and Neovascular AMD) compared to intermediate stages (Large Drusen). This pattern aligns with clinical understanding, as advanced AMD stages present more distinctive visual features.

The newly released BRAMD dataset provides a valuable resource for future research, contributing to the diversity of publicly available AMD datasets. This addition will help researchers develop and validate more robust models across diverse populations.

Overall, this research demonstrates the potential of foundation models to improve AMD detection from retinal images, with significant implications for clinical practice. By enabling more accurate, accessible screening, these models could contribute to earlier detection and intervention, potentially reducing vision loss from this common age-related condition.

Original Paper

Highlights

No highlights yet